WHEN A young Yorkshire solicitor named Harold Greenwood moved his practice to the Welsh town of Llanelly in 1898, his prospects seemed rosy enough. Having purchased Rumsey House, a large residence in nearby Kidwelly, he moved in there with his wife Mabel. She was the daughter of William Vansittart Bowater of Bury Hall, Edmonton, in Middlesex.

Yet it wasn't long before that roseate hue in the couple's skies soon gave way to a brooding cumulus of threatening cloud. For one thing, Greenwood's practice showed small sign of growth. And for another, his clients included a preponderance of “a less desirable element” moneylenders and their ilk.

His wife, however, was held in high esteem by her friends, for she took part in most of Kidwelly's social gatherings and could be seen regularly on a Sunday carrying her prayerbook and Bible to St. Mary's Church. Still, on the surface, the Greenwoods presented to the world the picture of a happy family.

After their move to Wales, the couple were blessed with four children, the eldest of whom was Irene. She came of age in 1919 and lived at home with her parents, with the other children away at boardingschool. At that time, the 47 year old Mabel Greenwood was in indifferent health. Her hair was streaked with grey and her face prematurely lined. She had endured a series of unaccountable fainting spells - and it was generally supposed that she had a weak heart. For some 16 years, Mabel had been the patient of Dr. T. R. Griffiths. Since the previous January, she had complained to him of pains around her heart and in her abdomen, but Dr. Griffiths put them down to what he called “the change of life” and prescribed some appropriate medicaments to help soothe the pains. During those six months, Mabel Greenwood suffered a marked deterioration in her health.

On Thursday, June 12th, 1919, she attended a meeting of antiquarians in the town hall, where people observed that she did not look at all well. Next day, she saw her dressmaker and mentioned that she was looking forward to a forthcoming holiday with her unmarried sister, Edith Bowater.

On the Saturday, she called on an old servant named Martha Morris, formerly a nanny to Irene. Mrs. Morris was another who noticed that Mabel looked very ill. On her way home, Mabel called at the Phoenix Stores and bought a bottle of Burgundy, which was to be served at lunch on Sunday. Then, that afternoon, decided to go to a tennis match at Ferryside, some five miles away. Her husband tried to persuade her to stay and rest, but she insisted that being in the open air would do her good.

The Reverend Ambrose Jones, Vicar of Kidwelly, was going on the same tennis trip. He left with Mabel in a carriage and they later returned by the same route, though at Kidwelly station Irene met her mother and accompanied her home. One visitor that June evening was a Miss Phillips. She later described the woman of nearly 50 as “seeming bright and with a vivd complexion. A lovely sort of pink.”

The next day saw the Greenwoods miss church. Irene sat and read a novel in the garden, her mother wrote some letters, while her father and a friend named Foy tinkered with the car. The cook, Margaret Morris, while preparing the lunch to be served with the Burgundy, noticed that the woman penning some correspondence looked drawn and tired.

The lunch was the customary joint with vegetables, followed by a gooseberry tart with custard, which was served at 1 o'clock. Later, Irene went out with her father's friend Foy for a driving lesson. Foy next saw and spoke to the mother again at around 3 o'clock, when she told him that she was glad her daughter was learning to drive. Half an hour later, Greenwood announced that his wife had diarrhoea. At 4.30 p.m., Hannah Williams, the maid, brought tea into the drawing-room. At 5 o'clock, Mabel and Irene went for a stroll in the garden, but the mother suddenly complained of suffocating pains. Greenwood gave her some brandy, which promptly made her violently sick.

He and Irene carried her upstairs to bed and Greenwood went for Dr. Griffiths, who lived across the street. The two men returned to find Mabel sitting on a couch and still vomiting in spasms. "It must be the gooseberry tart," she said, shuddering. "It always disagrees with me."

The doctor prescribed brandy and soda and left her. He and Greenwood then played several games of clock golf. When the doctor left, he sent from his surgery some medicine containing bismuth, which he had dispensed himself. Later that Sunday evening, he again looked in on Mabel Greenwood and found that she had stopped vomiting and seemed better.

Why no second doctor?

Miss Phillips also called at about 8 p.m. After just one look at Mrs. Greenwood, she decided to call in the district nurse, who lived only a short distance from Rumsey House. When the nurse arrived, she found that Mrs. Greenwood had collapsed. She wrongly assumed that the medicine by her bedside was that previously given to her by Dr. Griffiths, which was for a heart condition. The nurse promptly gave the patient a second dose, but there was no noticeable improvement.

The medicine for this "heart condition" later disappeared. It was thrown away, together with the large number of other empty bottles which had contained prescriptions by the doctor - as well as a large variety of patent medicines ordered by Mrs. Greenwood.

LATER THAT night, the nurse returned to see how Mrs. Greenwood was. And the doctor continued to look in during the hours before midnight, when the diarrhoea became uncontrollable, although he did not examine the excreta. Later, this omission assumed importance - and a great deal of what actually happened was called into question. By midnight, with the patient's condition growing visibly worse, Mrs. Greenwood asked if she was dying. And, at 1 o'clock in the morning, she told the nurse: “If 1 don't recover, Nurse Jones, I'd like my sister to look after the children and bring them up.”

With the patient considering the presentiment of death, it seems surprising that a second doctor was not summoned. In the confusion of the night, however, Irene finally asked her father to go again for Dr. Griffiths. For some reason never explained satisfactorily, Greenwood dallied most curiously on this short mission across the road, staying to chat to Miss May Griffiths, the doctor's sister. It was a good hour later, when an impatient Irene was on the point of going out to find what was delaying her father, that Greenwood at last reappeared. He was alone - and he was stifling a yawn.

As that slow, dragging night ticked away, the nurse became even more alarmed for the patient. She shook Greenwood awake. “You must fetch Dr. Griffths without delay," she told him. "This may be a crisis!”

Her words forced the solicitor to climb out of his bed and go again in search of the doctor. But Greenwood returned almost at once to say that the doctor was apparently fast asleep and he couldn't rouse him. Whereupon the tighttipped nurse, who'd had just about enough of this male nonsense, ran across the road and immediately succeeded in awakening the doctor's household. She promptly returned with him.

Mrs. Greenwood eventually died at about 3.30 on the morning of Monday, June 16th. Watched over by Nurse Jones and Irene, she had fallen into a coma, after taking some pills prescribed by Dr. Griffiths.

NURSE JONES brooded on Mabel Greenwood's death for some four hours. Then she took it upon herself to make a call at St. Mary's Vicarage. It was at 8 p.m. on that sunny day when the Reverend Ambrose Jones received the somewhat distraught woman and learned from her that Mrs. Greenwood was dead.

“She certainly seemed to be in reasonably good health when

I last saw her,” he said, expressing his shock at the night's swift march

of events. “I never realised that she was so desperately ill.”

Nor did a good many other people who had seen Mabel going about her visits and attending various functions in the Llanelly district. Before long, several very scurrilous assertions were being voiced. Suggestions that all had not been right in the Greenwood menage for a considerable time eventually gave way to outspokenly frank expressions, in which the word “murder” was muttered.

A number of root causes were responsible, following a confusion of carelessly timed incidents during Mabel Greenwood's last days. Yet there were some salient facts upon which these rumours were founded.

One of them was that Dr. Griffiths had, on the Monday, certified death as being due to valvular disease of the heart, meaning that his patient's heart was worn out. But then the story of the last medicines the doctor had prescribed with bismuth - and the pills his patient had swallowed during her last hours - became known through Nurse Jones and Miss Phillips, as well as others in the Greenwood household. Before long, there arose sufficient clamour about irregularities in the woman's death to make the coroner feel that he should order a postmortem.

Almost the first thing discovered by the medical experts was that the cause of death was certainly not due to the illness indicated on Dr. Griffiths' death certificate. Mabel Greenwood was interred on Thursday, June 19th, in the familiar churchyard of St. Mary's Kidwelly. A grief-stricken Irene Greenwood had been the one to register her mother's death. But her father had, accidentally or otherwise, omitted to send the formal certificate to the vicar, an omission that caused the man of the cloth to voice his personal misgivings and thus direct suspicion in the direction of the widower.

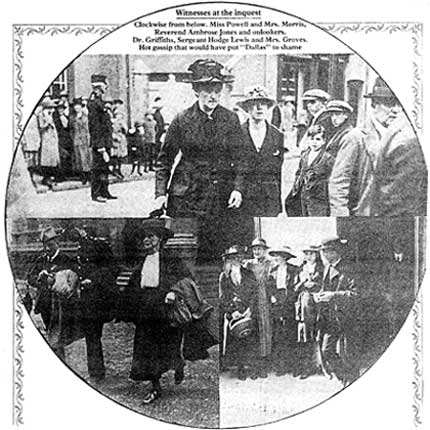

And Nurse Jones was another who didn't shut her ears to the spate of waspish spite about how Harold Greenwood had neglected his Mabel, the better to enjoy other female company. Indeed, she added a few strong views of her own. Spreading gossip in such a small community as Kidwelly meant that, before many days had passed, Sergeant Hodge Lewis felt himself compelled to call on Nurse Jones and ask her for some confirmation of what happened on the night of Mrs. Greenwood's death.

The sergeant took copious notes, which he showed to his superior, Superintendent Jones. The two police officers later cited these at the inquest. But like a good many people who live to regret having let their tongues wag too garrulously, the nurse suddenly felt it was time to beat a strategic verbal retreat in the face of a gathering storm of aroused anger, for which she had been partly responsible with her loquacious tongue. She now attempted to stop inflaming opinion against the solicitor. But she was like Pandora trying to shut her particular box of tricks. She failed - and with good reason.

She now saw in Harold Greenwood a possibly worthwhile suitor. She had certainly been visiting him since his wife's death, on the pretext of his attending to some legal business for her. On one occasion, she remained late with him to tell his fortune.

The Classic Murder Trial Was Held At Carmarthen Guild Hall

HAROLD GREENWOOD was physically fit and virile and Mabel had been a sick woman for a long time, so people were allowed to draw their own conclusions. However, Greenwood was a fool not to bow to Welsh prejudice, in that he became so obviously eager to enjoy the fruits of matrimony again, despite the fact that these had withered in his first marriage. Thus, while people were still expecting him to allow a reasonable length of time to elapse since Mabel's death, news came of his second marriage.

It produced a veritable bombshell - especially when it became known that he had been involved in a second offer of marriage. That bout of apparent lunacy occurred in this fashion.

The woman he married was Miss Gladys Jones. She was well over 30 and he had known her since her childhood, having been friendly with her family since 1898, when he first came to Llanelly. Her father was the owner of the Llanelly Mercury. And so, in September - only four months after Mabel's funeral - Harold Greenwood gave notice to the Llanelly registrar that he wished to wed Gladys Jones. Yet within a couple of days, he was penning a fulsome marriage proposal to May Griffiths, the doctor's sister! The letter ran:

“My dearest May,

I have been trying hard to get you this last fortnight, but no luck, always someone going in or you were out. Now I want you to think very carefully and to send me over a reply tonight. There are very many rumours about, but between you and 1 this letter reveals the true position. Well, it is only right that you should know that Miss Bowater and Miss Phillips between, them have turned my children against you very bitterly, why I don't know. It is only right that you should know this, as you are the one I love most in this world and I would be the last one to make you unhappy. Under the circumstances, are you prepared to face the music? 1 am going to do something quickly as I must get rid of Miss Bowater at once as 1 am simply fed up with her. Let me have something from you tonight.

Yours as ever,

Harold.”

This incredible missive leaves one boggling at Greenwood's naivete, since he had contracted to espouse another woman only hours before. What had come over him? He seemed hellbent on hurrying to disaster, for now the chattering tongues really had something to wag about. By Christmas, the topic of how Mrs. Greenwood had come to die reached a feverish climax. Greenwood and his new bride faced anything but a happy new year in 1920. The clamour refused to abate, so a harassed coroner eventually agreed to an inquest, hoping to clear up what was becoming a progressive mystery.

Actually, it was in October, 1919 - a month after Mabel's successor had been installed at Rumsey House that the police first warned Harold Greenwood of their likely intention to exhume Mabel's He appeared to take the news in his own hearty way, telling them: “Just the very thing. I am quite agreeable.”

But they didn't get around to signing an exhumation order until the following April was half over. And another two months elapsed before a twoday inquest was held on Mabel Greenwood - on June 15th and 16th, 1920. The apparent reason for the delay was that, when the body was exhumed, no trace of valvular disease was found. And the body was seen to be well preserved - in fact, it was too well preserved. For the doctors examining the remains discovered between a quarter and a half a grain of arsenic in the body!

Miss Phillips and Nurse Jones were among those who listened attentively to the coroner, Mr. J. W. Nicholas, when the inquest finally opened at the town hall in Kidwelly. These two interested parties and the others assembled there heard Mr. Ludform, who represented Harold Greenwood at the hearing in the latter's absence, comment on the seeming alacrity with which a suggestion of alleged foul play had come from the vicar. Mr. Ludform went on to accuse him of being among a crowd of gossips who had maligned his client.

In the course of the hearing, Miss Phillips was referred to by the absent Greenwood as “a treacherous busybody.” He dubbed her “The Kidwelly Postman,” from her readiness to disseminate gossip.

Sergeant Hodge Lewis's notes were read over. But by then, Nurse Jones had had months to think over her previous statements. When she was called to give evidence, she firmly denied saying to him: “You can look through me, Sergeant Hodge Lewis, I am telling the whole truth. I have had many cases like this. There was nothing unusual about the death.”

The police sergeant and the coroner could only stare at each other, then glare at the nurse's uptilted chin.

When George Jones, the jury foreman, led the 11 others back into the inquest room from their deliberations, he told the coroner in a loud voice: “We are unanimously of the opinion that the death of the deceased, Mabel Greenwood, was caused by acute arsenical poisoning, as certified.” Staring around and basking in the wave of the muttered acclamation rising from the public seats, he added dramatically: “And that the poison was administered by Harold Greenwood!”

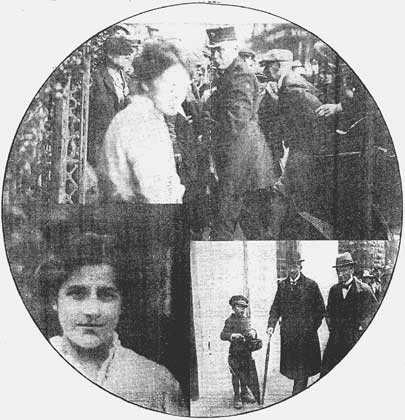

SHOUTING BROKE out. The populace of Kidwelly was giving vent to its feelings. And those feelings held only ill for the man who had been in such a haste to remarry. Greenwood was arrested and charged. But he was to wait over four months in jail before the trial could begin at Carmarthen Guild Hall. Meanwhile, he was briefed by Sir Edward Marshall Hall, K. C., one of the most notable advocates of his day.

Opposing Marshall Hall was another renowned advocate of the time - Sir Edward Marlay Samson, K.C. A blanket of fog hung over the Welsh valleys on that November 2nd, 1920, when Greenwood appeared before Mr. Justice Shearman.

From the first day when Greenwood, surrounded by mounted police, was taken in a carriage the short distance from the jail to the Guild Hall, he became the object of aloud expression of hatred on the part of the crowd.

But when the details of the Greenwoods' home life in Kidwelly were bared for harsh scrutiny, it was the prosecution who found that their case was resting on unsure motive. For the accused's stance was that he had been dependent on Mabel's money in order to keep Rumsey House in funds. His own income from the law was chancy, even in a good year. His dead wife, however, had had between £700 and £800 a year in her own right. This sum, in those days, was considerably more than a mere shockabsorber. It had left Greenwood able to live in the style to which he had become accustomed. By her death, he had lost by far the major part of his income, since his wife had been only a life tenant of her father's estate. On her death, the income had passed in equal shares to her children, whose trustees controlled it. In short, Greenwood simply couldn't get his hands on any capital. It was an important point to bear in mind when considering motive - or lack of it.

Sir Edward Marlay Samson, early in the trial, made a request for all witnesses to be ordered from the court, save for two medical men. Then the case got down to the nitty-gritty. It was the purchase from Mr. Bell, the Kidwelly chemist, of an arsenical compound in two separate packages, containing 60 per cent. arsenic and marketed under the brand of Cooper's Weedicide, which riveted the attention of lawyers and laymen alike. For the prosecution alleged that it had found sufficient evidence to show that, before the Sunday lunch on June 15th, 1919, Greenwood had placed some of that weed-killer in the bottle of Burgundy.

The Crown sought to show that the two purchases of weedkiller

from Mr. Bell, - one in February, 1919, the other in April - were more

than sufficient to kill Mrs. Greenwood. Also, if dissolved in the rubicund

Burgundy, neither taste nor colour would be noticeable - and 36 grains

of the weedkiller was only the equivalent of half a teaspoonful. But the

first real doubt was raised by Marshall Hall, who suggested to Dr. Griffiths

that he had made a fatal error by administering Fowler's solution of arsenic,

instead of bismuth, to Mabel Greenwood. He pointed out in his trenchant

manner that bottles containing both mixtures stood side by side in the

doctor's surgery. At this, the judge interposed gravely that, if this

was indeed true, it could amount to an accusation of criminal negligence.

Dr. Griffiths made a poor witness. He was uncertain and contradicted himself. He could not produce his prescription book - and the exact nature of the pills he had given his patient was in dispute. He had earlier, insisted that they were of morphia, but now claimed that they were opium based.

Dr. William Willcox (later Sir William) gave it as his opinion that death was due to heart failure consistent with prolonged vomiting and diarrhoea, due to arsenical poisoning. The fatal dose must have. been taken in soluble form between 1.30 and 6 p.m. He considered that at least two grains had been swallowed by Mabel Greenwood within 24 hours of her death.

The defence called as its poison expert a Colonel Toogood.

He stated that Mabel Greenwood died from morphia poisoning, following

acute gastroenteritis set up by eating, gooseberry skins.

Attempted to pick up the pieces of his life in Kidwelly, without success

Apart from the, vomiting, he said, there was no evidence

of symptoms of arsenical poisoning. Dr. William Griffiths of Swansea,

also for the defence, argued, that a quarter of a grain of arsenic in

a body was not conclusive evidence that it had caused death. He pointed

out that a living body could contain two and a half grains of arsenic

without, any ill effect.

With the medical evidence so obviously in conflict, the

public benches were silent for the first time. They looked hopefully at

Hannah Williams when the Welshspeaking maid declared on oath that Harold

Greenwood had spent half an hour In, the pantry before lunch on the fatal

Sunday, the inference being that he was occupied in poisoning the

wine. But Marshall Hall tore her flimsy evidence to tattered shreds in

no time, reducing her to tears and incoherence.

The benches among the public remained silent. And, if there

were still any doubts, it was Irene Greenwood. who laid them to rest.

She said she had drunk wine from the same bottle as her mother during

the Sunday lunch and had not felt even the slightest, bit queasy. Moreover,

she had drunk two glasses to her mother's one. Her evidence more or less

demolished the prosecution's case, which was built almost entirely upon

the administering of the Burgundy by an alleged poisoner.

DURING HIS summing-up, Mr. Justice Shearman warned the

jury against any show of bias. He told them: “It is your duty to concentrate

wholly upon the guilt or innocence of the prisoner.”

The jury was absent for two and a half hours before the

foreman delivered their written verdict. The words on the slip of paper

handed to the judge read:

“We are satisfied on the evidence of this case that a dangerous

dose of arsenic was administered to Mabel Greenwood on Sunday, June 15th,

1919. But we are not satisfied that this was the immediate cause

of death. The evidence before us is insufficient and does not conclusively

satisfy us as to how and by whom the arsenic was administered. We therefore

return a verdict of not guilty.” That trial result left any number of

pertinent questions unanswered. And, as the crowds melted away, there

were scowls on the faces of some who felt that they had been cheated by

a brilliant advocate. As for Harold Greenwood, the belief in his guilt

- in Wales, at least - persisted and remained a prime topic of discussion

for years. When he attempted to pick up the pieces of his life in Kidwelly,

he found that they simply couldn't be mended.

Even his old friend Dr. Griffiths had turned against him.

For, quite apart from testifying for the prosecution at the murder trial,

the good doctor was to sue Greenwood for some outstanding medical fees.

So the solicitor, forced to realise that he had become a social leper

and that the old life at Rumsey House was dead, eventually decided to

lose himself in an English rural district, where his face would be unfamiliar.

Curiously enough, one of the last things he did before

shaking the dust of Kidwelly from his heels for good was to write an article

for the magazine John Bull at the time of the trial of yet another

solicitor, Major Herbert Rowse Armstrong, of nearby Hayon-Wye, who was

convicted and hanged for the poisonmurder of his wife, Katharine. In that

article, Greenwood told the magazine's readership what it felt like to

be accused of murder.

So Harold Greenwood moved away - to die, nine years later,

in a Herefordshire: village, where .people knew him as “Mr.Pilkthgton”

He had little money and, broken in health, he had become a mere shadow

of his once ebullient self.

The cracker of jokes, lover of sporting wagers, good

friend of the fair sex - the latter had also turned against him when that

deep cloud descended over his life - had become lost in obscurity, bearing

a borrowed name.