Kidwelly Priory was always one of the smallest Benedictine cells founded by the Normans in medieval Wales. A daughter of the celebrated abbey of Sherborne in Dorset, it remained throughout its history a remote and little-known outpost of that great house, finding mention in the contemporary records only on rare and scattered occasions. There is not really enough surviving material to write a connected history of the priory; but the late and sorely missed Bill Morris was so passionately concerned with every conceivable aspect of the history of his beloved Kidwelly that it seemed impossible not to try to bring together what there was concerning the story of the priory in order to pay tribute to this devoted Carmarthenshire historian and very dear friend. I am deeply grateful to my friend, Dr F. G. Cowley, author of the best book on Welsh medieval monastic life, for so generously sharing with me his knowledge and expertise while I was preparing this essay.

It was Roger, bishop of Salisbury (d.1139), a Norman conqueror of the old Welsh commote of Cydweli, who founded the priory of Kidwelly; but for centuries before the Normans ever appeared, the neighbourhood had been the scene of Christian activity typical of the 'Celtic' era in the history of the Welsh Church. Two of the most illustrious native saints of the sixth century, Cadog and Teilo, or their early disciples, had laboured in the vicinity, judging by local dedications and placenames surviving from the pre-Norman period.1 The church at Cydweli itself appears to have been dedicated to St Cadog and was probably the mother church of the whole commote. Ancient wells in the district, to which pilgrims resorted throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, may also have been linked with the names of Celtic saints. The two best known among them were Ffynnon Fair ('Mary's Well') and Ffynnon Sul ('Sawyl's Well' or 'Solomon's Well'). It is very likely that the former was originally dedicated to a Celtic saint, only to be rededicated after the Norman Conquest; but the latter seems to have derived its name either from Sawyl Benisel, an early Welsh prince, or else from an early Welsh saint called Selyf or Solomon.2 However, little can be said with any certainty until the coming of the Normans about the turn of the eleventh century. Their arrival dramatically changed the whole situation.

Not until the reign of Henry I (1100-35) did the Normans effect secure possession of the commote of Cydweli through the medium of the King's chief minister, Bishop Roger of Salisbury.3 A man of humble origins and a priest of Caen, Roger rose rapidly in Henry I's service and was advanced to become bishop of Salisbury and justiciar and treasurer of the realm. As well as being an accomplished servant of State and Church, he was a notable castlebuilder, responsible for the formidable castles at Sherborne, Devizes and Malmesbury in addition to building the first castle at Kidwelly. He attained power in southwest Wales after the death in 1106 of Hywel ap Goronwy, the ruling Welsh prince of the commotes of Cydweli, Carnwyllion and Gwyr, when the King took prompt steps to ensure the interests of the Crown by replacing Hywel with reliable Norman rulers. He granted Cydweli and Carnwyllion to Bishop Roger, who quickly proceeded to organize them into the marcher lordship of Kidwelly. Early in the process, at a date before 1115, he embarked on an ecclesiastical enterprise that was typical of the early Norman conquerors of south Wales when he founded a priory of Benedictine monks as a further instrument, along with castle and borough, of conquest and consolidation. Monasteries after the Celtic fashion had been a familiar and much venerated feature of the Welsh scene. Since the sixth century4 these Latin style Benedictine priories were a novelty distinctly unacceptable to the native population. It was usual for them to be founded at the expense of an earlier dedication to the Celtic saints, whose memory was so inextricably intertwined with the people's affections, and by expropriating existing Welsh ecclesiastical endowments.5 This appears to be what happened at Kidwelly. The original dedication of the local church to St Cadog was changed to St Mary the Virgin, a particular favourite with the Normans. Furthermore, Roger of Salisbury made a grant of land to his favoured Benedictine abbey of Sherborne to enable it to found a daughter cell at Kidwelly. Sherborne was an ancient AngloSaxon abbey, which had been the seat of a diocese until the Normans moved it to Salisbury, and Bishop Roger may well have wished to give a discreet reminder that he had not overlooked its former status or forgotten its interests. So, on 19 July in some year between 1107 and 1114, possibly about 1110,6 on behalf of the souls of his patron Henry I, Queen Matilda and their sons, and those of his parents, himself, and his ancestors, he granted to the 'Holy Church of Sherborne' and its prior, Turstin (or Thurstan), and his successors one carucate of land at Kidwelly.7 A carucate consisted of as much land as could be ploughed with a single plough and eight oxen in a year and might amount to either 80 or 120 acres by the Norman number. Roger specified the boundaries of his grant in some detail: it was to run from the ditch of the new mill to the house of one Balba, and thence to the river, running through the alder grove, to the way and from the way as the river ran to the sea; and it also included the hill called the hill of Solomon. It was to be exempt from all secular exactions, tithes, and other payments, and its monks were to enjoy the right to keep their own pigs free of pannage (the payment made to the owner of the woodland for this privilege), to have wood from the lord's forest, and freedom to pasture their animals within his demesne. This grant was made in the house of the castle of Kidwelly - not the present stone castle, of course, but an earlier one made of earth and timber - and was attested by a number of witnesses, including among them one Alwyn, described as priest of the vill. Three days later, Bishop Roger, with the consent of Wilfred, bishop of St David's (1085-1115), dedicated the cemetery at Kidwelly; and, at this dedication, the burgesses, English, French, and Flemish, gave their tithes at Penbre and Penallt to Sherborne.8

Later on in the twelfth century, during the episcopate

of David, bishop of St David's (1147-76), Maurice de Londres, to whom

the lordship of Kidwelly had passed c.1135, gave and granted to God, St

Mary of Kidwelly, and the monks of Sherborne twelve acres round the church

of St Cadog which adjoined the lands of St Mary.9

There also exists a document recording a grant made to Sherborne by Richard

son of William, another member of the de Londres family, in the time of

Bishop Bernard of St David's (1115-47), of Richard's churches of St Ismael

and Penallt, the church of All Saints at Kidwelly (tentatively identified

as the church of Llansaint), and the church of St Illtud at Penbre.10

This was a mysterious transaction, and the rights conferred by it did

not remain permanently in the possession of Kidwelly Priory. Thus was

the priory first founded and endowed. It was at all times a tiny Benedictine

cell; and yet it is testimony to the tenacity of its own monks and those

of Sherborne that they succeeded in retaining their possessions throughout

all the vicissitudes of four hundred years until the mother house was

dissolved in 1539.

Kidwelly was one of a number of little priories founded

by the Normans in south Wales. Some of them, like Monmouth, Abergavenny,

Llangennith, or St Clear's, were daughter priories of Continental monasteries

looked upon with favour by the Normans; others, such as Kidwelly, Brecon,

Ewenni, or Cardigan, were affiliated to English houses dear to the conquerors.11

All of them were associated with foreign conquest in the minds of the

native Welsh population, from whom they were never able to gain support

and rarely able to recruit any novices. Almost without exception, those

monks associated with Kidwelly whose names are known us seem to have been

Sherborne monks, originating from Dorset or neighbouring counties in the

west of England.12 Throughout their history

the numbers of inmates at these priories remained small: Kidwelly never

appears to have had more than a prior and one or two monks at any one

time. They were not intended to introduce full conventual life but only

to establish a monastic presence in the neighbourhood, so as to safeguard

the priory's possessions and collect its rents and profits.

Another function which the priory carried out was to serve

as the parish church of the borough. As we have seen, the English, French

and Flemish burgesses were associated with the endowment of the priory

from the start, and a parish on Norman lines may early have been carved

out to include the borough and its associated lands. In providing regular

services and acting as a focus for the administration of the sacraments,

the priory assumed the role previously carried out by the former mother

church of the commote. At the time the priory was founded there was an

existing priest of the township called Alwyn (see above). His duties may

subsequently have been performed by the monks, though it seems more probable

that from an early stage a stipendiary priest, or even a vicar, may have

been employed for the purpose. There was certainly a vicar at Kidwelly

early in the fourteenth century, when he is referred to in a court roll

of 1310 as Thomas the Vicar,13 but there

may have been one there at a much earlier period. Again, there was a close

connection between the priory and the chapel built in the stone castle

between about 1290 and 1310, and that association may well have existed

long before in the person of a chaplain serving the inmates of the castle

built nearly two centuries previously.

In view of the circumstances in which the priory was founded,

the origins of its monks, the nature of its functions, and its close associations

with foreign overlords, it was not surprising that the Welsh population

of the surrounding area should view it with the same hostility that they

showed towards other Norman institutions like the castle and the borough.

Throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, conditions remained extremely

unstable, with the Welsh refusing to knuckle under to Norman rule. On

more than one occasion their stubborn resentment erupted into open warfare

against their masters, in the course of which castle, borough and priory

were subjected to damaging attacks. The battle fought against the Normans

by the Princess Gwenllian may have ended in defeat in 1136 but it is deservedly

famous in Kidwelly's annals. Later on, the castle was demolished by Cadwgan

ap Bleddyn, only to be seized and strengthened in 1190 by the Lord Rhys.

In 1215 another Rhys, one of the Lord Rhys's descendants, swept through

Kidwelly and burnt it again. By 1223 the power of Llywelyn ab Iorwerth

('the Great') was signalled when his son, Gruffydd, burnt the town, church,

and religious house. Since most of the buildings were of timber construction,

however, they may have been quickly rebuilt. In 1257 Llywelyn ap Gruffydd

('the Last') brought a powerful army to south Wales and ravaged the English

settlements at Kidwelly and elsewhere. The emergence of this strong Welsh

power in Gwynedd meant that the threat to English rule in south-west Wales

had assumed new and dangerous proportions.14

This, in turn, provoked a vigorous English reaction, as

a result of which the rule of king and marcher lord was to be much more

firmly imposed on Wales during the later thirteenth century. In 1274 the

lordship of Kidwelly came into the hands of the capable Pain de Chaworth,

who inherited it from his mother, Hawise. He began ambitious building

operations on a new stone castle, which, when he died in 1279, were continued

by his brother Patrick (d.1283), whose daughter and heiress, Maud, married

the wealthy and influential Henry, earl of Lancaster (1281-1345), in 1298.

Between them, these three lords constructed the mighty concentric castle

which still stands, awesome and forbidding, on the west bank of the Gwendraeth.

The building of Kidwelly Castle coincided with Edward I's Welsh campaigns

of 1276-7 and 1282-3, launched to destroy the menacing power created by

the princes of Gwynedd. By 1283 the authority of English king and Norman

lord was far more securely riveted on to the subject population than it

had ever been.

Interestingly enough, it is from Edward I's reign that

there survive two sources which shed some fascinating gleams of light

on the destinies of Kidwelly Priory. The first is the register of Edward's

archbishop of Canterbury, John Pecham, who undertook a largescale visitation

of the Welsh Church in 1284 in the immediate aftermath of the conquest

of Wales. Pecham was an austere Franciscan friar holding strict views

about the necessity for maintaining the highest standards of fidelity

to the monastic vows, and among the churches and monasteries he visited

in south Wales was Kidwelly Priory, where he discovered a highly unsatisfactory

state of affairs.15 The prior at the time

was Ralph de Bemenster (Beaminster, co. Dorset), who, 'because of his

manifest faults', was sent back to Sherborne in disgrace by Pecham. Barely

a month later, nevertheless, the abbot of Sherborne had the temerity to

reappoint him. Pecham was understandably outraged and ordered the abbot,

under pain of excommunication, to recall the errant prior, subject him

to severe monastic discipline, and in the meantime forthwith to appoint

a worthy candidate to take charge at Kidwelly. This was an intriguing

episode, about which it would have been helpful to have rather more information.

As it is, the temptation to speculate about what the circumstances were

is irresistible. It may be that Prior Ralph had been a troublesome monk

whom the abbot of Sherborne was not sorry to banish across the Bristol

Channel to a distant outpost in Wales. Alternatively, it may be that Ralph,

unsupervised and kicking his heels in exile, had allowed his deportment

and behaviour to degenerate to a point at which they became unworthy of

his monastic vows. Whatever the explanation, the episode offers an example

of a problem not unfamiliar to monastic houses: how to maintain appropriate

standards in a tiny and isolated cell, situated at a considerable distance

from its mother house. One cannot help wondering, either, whether or not

such a situation occurred more than once at Kidwelly!

The other near contemporary source of informer is the Taxatio

of Pope Nicholas IV, compiled in 1291 for purposes of papal taxation.16

The main source of income recorded for the priory came from the tithes

of the parish of Kidwelly, estimated to be worth 20 marks (£13.6s.8d.);

but it also possessed one carucate of land with rents and perquisites,

valued at £2.l0s.0d., together with five cows worth five shillings.

Presumably, the monks still continued to farm much of their land by means

of serfs or hired labourers. Evidence from other late thirteenth century

and early fourteenth century sources, however, suggests that the priors

were then, and possibly had been for some time, leasing out lands to tenants.

Hugh, abbot of Sherborne (1286-1310), certainly leased to one Llywelyn

Drimwas and his wife, Gwenllian, 'Seint Marie lond' for life in return

for an annual render of 12d., payable at Michaelmas, on condition that

they were not allowed to sell, mortgage, or alienate the land, which was

subsequently to return to the prior.17

The half-century or so following the Edwardian Conquest

and settlement of Wales, 1283-4, seems to have been a period when the

Church in Wales was generally in a relatively flourishing state.18

The same may very well have been true of the borough and priory of Kidwelly.

After the decisive defeat of the princes of Gwynedd and the suppression

of the risings of Rhys ap Maredudd in the south in 1287 and Madog ap Llywelyn

in the north in 1294-5, there was considerably less risk of Welsh insurgency.

A number of the Welsh were sufficiently conciliated to move in as settlers

to boroughs such as Kidwelly. In the surviving fragments of Kidwelly court

rolls from the fourteenth century, unmistakably Welsh names, like those

of Llywelyn Drimwas and Gwenllian already mentioned, are to be found among

the priory's tenants people like John Owen, Agnes ap Owen, Ieuan ap Res

Wyt, Gwenllian his wife, and Ieuan ap Ianto.19

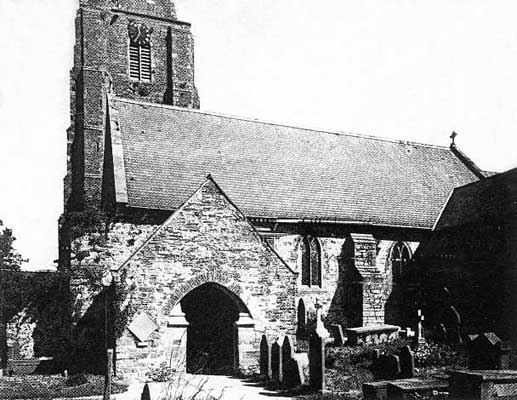

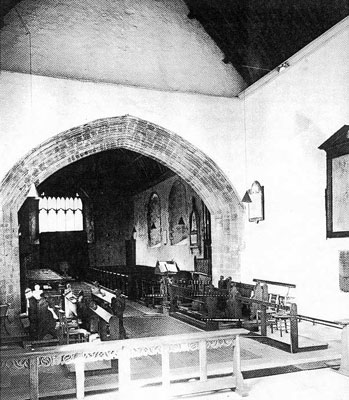

The priory church itself was ambitiously rebuilt early in the fourteenth

century When the famous architect, Sir Gilbert Scott, surveyed

the church in some detail in 1854, before any largescale restorations

had been undertaken, he characterized it as one of the most remarkable

churches in south Wales. He particularly admired the ample open space

of its aisleless nave thirty-three feet wide overall together with its

sturdy and handsome tower. He concluded that the original fourteenth century

nave had been nearly twice as long as the present one, so that the tower

and the porch had then been mid way between the transepts and the western

end of the church. In spite of the pronounced differences between the

rich flowering tracery observable in the chancel, Accompanying the building of the church there may also

have been a reconstruction of the modest conventual buildings. The priory

would naturally have been primarily if not solely responsible for any

work of this kind which was undertaken. Since there would never have been

at any time more than two or three monks at Kidwelly, and their possessions

were so limited, no large or elaborate conventual accommodation would

have been necessary. There have never been any excavations on the site

to reveal possible foundations of such buildings and, as far as is known,

none is planned because the existing graves fit so tightly around the

church. However, early in the twentieth century, on the north side of

Causeway Street, to the west of the priory, there survived a medieval

dwelling known as the 'Prior's House'. It was described by the Commissioners

of the RCAM in 1916 as 'only a fragment of a large house which, with its

garden and appurtenant buildings, doubtless formed part of the Benedictine

priory of St Mary'.25 A sketch of the same

house which had appeared in Archaeologia Cambrensis half a century

earlier showed it to be about double the size it was in 1916.26

Even in the latter year, much of the house had been renewed and significantly

modified; since then it has been entirely pulled down (1932). These premises

would appear to have been large enough to have housed the monks and their

attendants in some comfort. The house was dated by the RCAM to about the

end of the thirteenth century; but it is not at all improbable that its

construction formed part of the rebuilding programme of the early fourteenth

century.

That enterprise may have been the last bold flourish of

an era of prosperty. There is good reason to believe that soon afterwards

the monastic cell at Kidwelly, like most of the other religious houses

of England and Wales, entered upon a trying period of crisis and difficulty

between c.1340 and c.1440.27 Deterioration

in the climate, a declining population, falling demand, and erratic but

generally downward movements of prices made economic conditions much more

unfavourable for all landowners, lay and monastic. The Hundred Years War

between England and France, lasting from 1357 to 1453 with long intervals

of truce, imposed a number of additional burdens; the outbreak of the

Black Death, 1349-51, followed by further visitations of pestilence in

1361, 1369, and later, reduced the population and income of monastic houses

as well as of the country in general; and, finally, in the first decade

of the fifteenth century, there burst upon Kidwelly, in common with many

other parts of Wales, the devastating Glyndwr Rebellion. It is difficult

to estimate the consequences of this series of calamities for Kidwelly

Priory, because it so rarely warranted a mention in contemporary records.

There are, nevertheless, a few slight indications that it may have suffered

the same adverse effects as other monasteries did in Wales in general

and in Carmarthenshire in particular.28

Economically speaking, even by the end of the thirteenth

century, Kidwelly had encountered some difficulty in exploiting its small

estate in the traditional way and had begun leasing its land to tenants.

Fragmentary court rolls from the fourteenth century provide further evidence

of problems with defaulting and troublesome tenants.29

In an attempt to offset its troubles somewhat, the priory managed to obtain

a grant of three messuages and twentythree acres of marsh and meadow from

Dame Maud of Lancaster; the text of whose grant includes a variety of

interesting placenames.30 As far as the wars

with France were concerned, Kidwelly escaped many of the worst consequences

befalling those. Benedictine priories whose mother houses were situated

in France and which, as a result, were periodically seized by the Crown

throughout the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and some of which

were eventually suppressed altogether.31

As a daughter of Sherborne, Kidwelly was spared such a fate; but all the

same it experienced the effects of heavier taxation and inflation as a

result of the wars. No precise indication of the impact upon it of plague

and disease has come down to us. What we do know is that epidemics badly

affected the lordship of Kidwelly32 and,

since such outbreaks tended to be at their worst in lowland areas and

estuaries, it is unlikely that the inmates and tenants of the priory escaped

unscathed. The only shred of information available about numbers there

at this time is that one solitary monk is recorded as having been liable

to pay poll tax at Kidwelly in 1377.33 It

may also be significant, perhaps, that the priory sought to add to its

lands in 1361, a year in which there had been a severe outbreak of plague.

The Rebellion of Owain Glyndwr, on the other hand, is certainly

known to have hit the lordship, borough and priory of Kidwelly hard. An

attack was launched on the town in October 1403, when its walls were breached

and the castle subjected to a three week siege, though it did not succumb.

There followed uneasy years when the castle and the town, isolated in

the midst of a hostile and menacing countryside, found that their food

supplies were highly precarious. They lived in dread of further attacks

from joint FrancoWelsh forces in 1405 but, fortunately, were bypassed

by them.34 Serious difficulties continued

long after the Rebellion was over. In 1428 the reeve's litigation over

the withholding of tithes of lambs, wool and cheese from the prior of

Kidwelly on the part of a cleric, John Sandon, of the collegiate church

of Leicester, and a number of laymen from the diocese of St David's.35

Some years later, in 1444, a charter granted to the borough of Kidwelly

by Henry VI declared that the burgesses 'had suffered no small losses

and burnings of their houses and divers oppressions which the Welshmen

of their malice' had inflicted upon them, with the result that the old

borough was 'waste and desolate'.3637

Damaging and longlived though some of the consequences

of the Glyndwr Rebellion were, there were none the less signs of recovery

on the part of lay and clerical society from c.1440 onwards, and possibly

earlier. That very charter of 1444, which described so graphically the

destruction wrought by rebellion, was itself a symptom of slowly returning

selfconfidence. Equally significant were the growth of the cloth trade

in and around Kidwelly38 and the brisk trading

links created between the port and Bristol, the emporium of south Wales

and the West Country.39 Although the 'old

borough' immediately adjacent to the castle remained largely desolate

for along time, this worked to the advantage of the 'new town' in the

environs of the priory. Many people moved in there during the fifteenth

century, as they did to a comparable 'new town' at Pembroke.40

Moreover, the priory church and those who worshipped there may well have

made vigorous efforts, on a par with the attempts being made in other

parts of Wales, to add to the prosperity of their church and community

by seeking to attract large numbers of pilgrims.41

Kidwelly was admirably sited for the purpose. It had for centuries been

the chief church of the commote and, later, of the lordship and rural

deanery. The administration of the Lancaster lordships was centred at

Kidwelly and that drew many individuals there on business of various kinds.

It stood on the main land route through south Wales and was a port of

some consequence for those who travelled by sea. Quite apart from being

one of the most important staging posts by land and sea for pilgrims journeying

to the premier shrine of Wales at St David's, Kidwelly had attractions

of its own to offer the faithful. Chief among them was the lifesized alabaster

statue of the Holy Virgin and the child Jesus, which had been placed in

a niche on the south wall of the chancel at the entrance to the south

transept, either in the fourteenth century or the fifteenth.42

In an age when the cult of the Blessed Virgin Mary was rapidly growing

in popular esteem, the alluring and elegant image was a drawing card of

some celebrity.43 Adding to its appeal for

pilgrims were Ffynnon Fair and other holy wells nearby. Furthermore, a

rood screen, or possibly even two rood screens,44

were set up in the church in the fifteenth century to enhance its attractiveness.

Such screens were becoming highly regarded in later fifteenthcentury Wales

and exemplified the increasing appeal to votaries of the cult of the stricken

Saviour. The existence at Kidwelly of two features expressive of the contemporary

trend of devotion towards the Virgin and her Son45

could conceivably have been a source of uncommon attraction for pilgrims.

The survival of the episcopal registers of the diocese

of St David's for parts of the fifteenth century and the early sixteenth

enables us to recover the names of some of the monks and clergy associated

with Kidwelly. The names of two fifteenthcentury priors can be gleaned

from this source: John Sherborne in 1482, and John Henstrige, presented

to succeed him in 1487 by the abbot of Sherborne. If the advowson of the

priory, as might be expected, lay in the hands of the abbot of Sherborne,

the right to present to the vicarage ordinarily rested with the prior.

It was he who presented Bernard Tyler in 1407, John David in 1482, John

Cheyney in 1491, and John Griffith in 1502. The lastnamed had, in 1496,

been ordained a priest on a title of Kidwelly Priory, and was still vicar

there in 1534. In October 1490, however, for some inexplicable reason,

it was Hugh Pavy, bishop of St David's (148596), who collated Master John

Gunva (?Gwynfe), though the unfortunate man was dead by May of the following

year.46 One of the interesting features of

these fifteenth century vicars was the mixture of Welsh and English names

to be found among them, possibly reflecting the mixed nature of the population

whom they served. The priors, however, continued to be Sherborne monks.

Whatever success may have attended the priory's efforts

to mend its fortunes seems only to have been shortlived. For the last

two decades of the fifteenth century and the first quarter of the sixteenth

century it appears to have been once again in a sadly reduced state. By

this time the trade of the port was being adversely affected by the gradual

silting up of the estuary which was taking place.47

Much more devastating for the priory itself was that on 29 October 1481

it was struck by lightning,48 which must

have caused acute problems and constituted a serious setback to all its

attempts to attract pilgrims. It seems likely that it was at this time

that the western end of the nave met with disaster and, in consequence,

lay in ruins for many years. In 1513 Kidwelly Priory was one of a number

of smaller monastic houses in the diocese exempted from the payment of

tenths on account of its poverty, and was again excused in 1517, at which

point all the prior's temporal goods were also exempted.49

On 20 April 1524 it was described as 'much bound in .from great and manifest

decay'. So sad was its plight that Richard Rawlins bishop of St David's

(1523-36), had to take the drastic step of empowering the vicar, John

Griffith, and a layman, Robert France, to sequester all the tithes and

other profits of the church and priory and devote them to the repair of

the chancel of the church and the house of the priory.50

Conceivably, it was now decided to write off the damaged western portion

of the nave and do only a patching job by closing up the nave with the

present western end and inserting a Perpendicular window. The other possibility

is that this section of the nave was demolished at the time of the Dissolution,51

though it is not easy to see why that should have been necessary, and

if the church were then going to be reduced in size, one might have expected

that the chancel, not the nave, would have been taken down, as happened

at Margam or Talley or Chepstow. Whatever the reason for the decision,

reducing the nave by nearly half severely impaired the balance and symmetry

of the church.

Like all the other religious houses in the country, Kidwelly

Priory was now nearing the end of its history. In 1534 Henry VIII established

himself as Supreme Head of the Church on earth, and under the terms of

his Act of Supremacy he required all the clergy, including monks, to take

an oath of loyalty to him. The two monks at Kidwelly, John Godmyston,

the prior, and his companion, Augustine Green, duly took the oath, as

did the vicar of Kidwelly, John Griffith, and his unnamed cantarist.52

In the following year, commissioners for the diocese of St David's, acting

on behalf of the King, drew up a list of the possessions of the realm,

known at the Valor Ecclesiasticus.53 The

priory at this time possessed temporal tenements and demesne lands worth

£6.13s.4d. a year. Most of its possessions seem to have consisted

of twentyeight tenements of urban property concentrated in the 'new' town54

which had increasingly grown up in the vicinity of the priory. Its spiritualities,

i.e., the income derived from churches at Kidwelly and the neighbourhood,

were worth a good deal more, being valued at £31.6s.8d. Out of a

total income of £38.0s.Od., a number of deductions in the form of

fees and pensions, amounting to £8.10s., had to be made annually,

leaving a net income of £29.l0s.0d.55.

Most of the smaller monasteries were dissolved in 1536;

but Kidwelly, as a daughter of Sherborne, survived until the disappearance

of its mother house in 1539. At that point, there was no mention of either

John Godmyston or Augustine Green, who were there in 1534, and only the

then prior, John Painter, was left to be assigned an annual pension of

£8.56 A few years later, in 1544, George

Aysshe and Robert Myryk, king's yeomen and purveyors of wines, were granted

a lease for twenty?one years of Kidwelly priory or cell, together with

certain tithes and pensions accruing from Pen-bre rectory.57

It can hardly be claimed that the disappearance of the little Benedictine

priory was a conspicuous loss to the religious and devotional life of

the Kidwelly neighbourhood. Its members had always been too few in number

for it to have set a notable example of worship, piety, or learning. Nor

is there any surviving evidence of its having fulfilled the social duties

of providing charity, education, hospitality, healing, or relief for the

aged, though that is not necessarily to say that it did not do so.

The possessions of the priory were not the only ecclesiastical

property in Kidwelly to suffer expropriation; with the suppression of

the chantries in Edward VI's reign came further despoliation. There had

been a chantry in the castle since the fourteenth century and, if it still

existed,58 it presumably passed into the

possession of the Crown in 1549. Another larger and more important chantry,

dedicated to St Nicholas, patron saint of mariners, had been founded in

the parish church, possibly in what is now the clergy vestry on the north

side of the chancel.59 Late in the reign

of Henry VIII, when the chantries were first surveyed in 1546, it was

recorded as being worth £4.0s.2d., of which 31s.2d. was paid as

a stipend to the chantry priest.60 It was

again included in the Chantry Certificate of 1549,61

and its possessions were itemized in detail in a lease of 1549 granted

to John Goodale for a term of twentyone years.62.

Nearly a hundred years later in 1641, the lands formerly belonging to

the dissolved chantry were once more the subject of extensive examination.63

Additionally, the parish may also have suffered the depredation of some

of its church goods in 1552, when a certificate of them was drawn up by

Crown commissioners.64

In spite of the heavy hands laid on the possessions of

the priory and the chantry, that was not the end of the connection between

the priory church and the town. Though the monastic community had been

disbanded, the need for a parish church to serve the parishioners still

remained. The priory church was therefore retained by the townspeople

for this purpose, as indeed were many other former Benedictine churches

elsewhere in Wales. The parishioners, however, only had control of the

nave of the church; responsibility for maintaining the chancel rested

with those who leased the living from the Crown. These lessees usually

showed a marked reluctance to spend money on keeping the chancel in good

order. In 1597-8, the AttorneyGeneral, Edward Coke, was obliged to bring

the lessee of Kidwelly, Francis Dyer of Somerset, to the Court of Exchequer

in an endeavour to induce him to fulfil his duty in this respect.65

No means exist, unfortunately, of discovering the outcome of this litigation;

though it may be significant that when Gilbert Scott examined the church

in mid-nineteenth century, he declared that the roof of the chancel, which

he dated to the reign of James 1, was then the part of the church in best

condition. However, it is also known that in 1672, and again in 1684,

churchwardens' visitation replies reported the church as being out of

repair and fallen down since 20 June 1658, when it had again been struck

by lightning. Not until 1715 do the same sources record the church as

being lately rebuilt and in good repair, though its spire was still suffering

from lightning damage.66 Problems with the

fabric continued until late in the nineteenth century when the church,

yet again the victim of a lightning strike in 1884, was comprehensively

rebuilt.

Of all the features of the postReformation history of the

church at Kidwelly none, perhaps, was more individual or astonishing than

the survival of the alabaster figure of the Madonna and child and the

extraordinary reverence shown towards it for so long by the women of the

parish. In spite of the Protestant hostility towards images in the sixteenth

century and repeated orders issued for their removal, the figure seems

to have survived into the seventeenth century. It was then said to have

been 'exposed to the elements' and to rough handling by the Puritans,

leading to mutilation and the disappearance of the head of the child Jesus,

the left arm of the Virgin, and one of the birds.67

Nevertheless, it must still have commanded the devotion of many of the

parishioners and appears to have been replaced, presumably after the Restoration

of 1660, in a niche above the south door of the church under the shelter

of the porch. Until well into the nineteenth century, women curtsied to

it on entering and leaving the church, dipping their fingers in an ancient

holywater stoup, into which water had been surreptitiously poured.68

The image was still in situ in 1846, when John Deffett Francis made a

sketch of it - now in the National Library of Wales - in the course of

a visit paid by the Cambrian Archaeological Association.69

However, during the vicariate of the Reverend Griffith Evans (1840-80),

an incumbent who seems to have held stern Low Church and puritannical

convictions,70 and who may well have been

deeply disturbed by what he interpreted as vestiges of popery in his parish

at a time when High Church and even Romanist tendencies appeared to be

everywhere on the increase in the Anglican Church, he ordered the removal

of the offending image and had it buried in the graveyard c.1865-70. This

created so great a popular outcry that it was dug up again and was shown

to the Cambrians in the course of their visit in 1875. It was later stored

in a room under the tower, where it was subjected to rough handling by

'thoughtless Philistines'.71 About the year

1900, however, it was reliably reported as being preserved in the vestry

of the church.72 The reverence paid to the Madonna was not the only symptom

of markedly conservative tendencies among the local population. A number

of holy wells, including among them Ffynnon Fair, Ffynnon Sul, Pistyll

Teilo, and others, were regularly resorted to until early in the twentieth

century by those who sought healing or good fortune. Such customs reflected

the persistence among the parishioners of old religious practices, less

and less clearly understood with the passing of the years. It has rightly

been pointed out that neither Reformation doctrine, nor the teachings

of Puritans and Dissenters, made such headway among the population. The

first Nonconformist chapel in the town, Capel Sul, was not opened until

as late as 1785, and the townsfolk remained loth to accept religious change.74

The priory of St Mary may have disappeared in 1539 but the influence of

the saint to whom it had been dedicated lived on for long in the folk

memory of the town.

in the Decorated style of architecture. Some of its features, including

the wave moulding and the flattish fourleaved flower, are similar to the

motifs favoured by the master of the Decorated style in Wales-Bishop Henry

de Gower of St David's (1328-47).20 This

would not necessarily indicate that the bishop himself had had a hand

in the work, but might give us approximate dates when it was undertaken.

The dates of his episcopate, strikingly enough, coincide very closely

with the estimate given by Sir Gilbert Scott, who believed that the building

had been undertaken about the end of Edward's reign (1307-27) or early

in that of Edward III (1327-77).21 No evidence

exists to show who took the initiative in planning or funding this largescale

project, but it could well have been a joint responsibility. The abbey

of Sherborne, it might reasonably be supposed, would have had a considerable

role to play in overseeing the enterprise. Again, in view of the close

connections between the priory and the castle, the wealthy lord of Kidwelly,

Henry earl of Lancaster, who had earlier centred the administration of

the Lancaster lordships of the area at Kidwelly, might also have contributed

handsomely. By no means least may have been the share taken by the burgesses

of Kidwelly in the task of beautifying and extending their own priory

church, especially since the borough had been expanding in the fourteenth

century around the nucleus of the settlement founded in conjunction with

the priory.22 At all events, whoever had

the vision for the venture and bore the costs of it, the outcome of the

efforts of all or some of these interested parties was the erection of

a spacious and beautiful church, the general features of which, though

greatly modified and reconstructed over the centuries, are still with

us, in spite of its having been severely damaged by lightning strikes

on at least three occasions in 1482, 1658, and 1884.

in the Decorated style of architecture. Some of its features, including

the wave moulding and the flattish fourleaved flower, are similar to the

motifs favoured by the master of the Decorated style in Wales-Bishop Henry

de Gower of St David's (1328-47).20 This

would not necessarily indicate that the bishop himself had had a hand

in the work, but might give us approximate dates when it was undertaken.

The dates of his episcopate, strikingly enough, coincide very closely

with the estimate given by Sir Gilbert Scott, who believed that the building

had been undertaken about the end of Edward's reign (1307-27) or early

in that of Edward III (1327-77).21 No evidence

exists to show who took the initiative in planning or funding this largescale

project, but it could well have been a joint responsibility. The abbey

of Sherborne, it might reasonably be supposed, would have had a considerable

role to play in overseeing the enterprise. Again, in view of the close

connections between the priory and the castle, the wealthy lord of Kidwelly,

Henry earl of Lancaster, who had earlier centred the administration of

the Lancaster lordships of the area at Kidwelly, might also have contributed

handsomely. By no means least may have been the share taken by the burgesses

of Kidwelly in the task of beautifying and extending their own priory

church, especially since the borough had been expanding in the fourteenth

century around the nucleus of the settlement founded in conjunction with

the priory.22 At all events, whoever had

the vision for the venture and bore the costs of it, the outcome of the

efforts of all or some of these interested parties was the erection of

a spacious and beautiful church, the general features of which, though

greatly modified and reconstructed over the centuries, are still with

us, in spite of its having been severely damaged by lightning strikes

on at least three occasions in 1482, 1658, and 1884.

as contrasted with the plain, severe and narrow windows of the tower,

Scott was convinced that the church was all part of a single build undertaken

about the third decade of the fourteenth century.23

This view was robustly challenged by E. A. Freeman, who believed that

the tower had been builtin the thirteenth century, being in keeping with

other south Welsh towers built in that century, and that the nave had

been added to it in the fourteenth century.24

as contrasted with the plain, severe and narrow windows of the tower,

Scott was convinced that the church was all part of a single build undertaken

about the third decade of the fourteenth century.23

This view was robustly challenged by E. A. Freeman, who believed that

the tower had been builtin the thirteenth century, being in keeping with

other south Welsh towers built in that century, and that the nave had

been added to it in the fourteenth century.24

Eventually,

in the 1920s it was repaired and replaced, first on the south wall of

the nave above the Memorial to the fallen of the First World War, and

later, in 1971, in a niche specially made for it on the south side of

the east window of the church.73 Even today,

in spite of its past misfortunes, it retains its impressive beauty and

serenity, which undoubtedly help to explain why, for so long, it retained

the devotion of Kidwelly people.

Eventually,

in the 1920s it was repaired and replaced, first on the south wall of

the nave above the Memorial to the fallen of the First World War, and

later, in 1971, in a niche specially made for it on the south side of

the east window of the church.73 Even today,

in spite of its past misfortunes, it retains its impressive beauty and

serenity, which undoubtedly help to explain why, for so long, it retained

the devotion of Kidwelly people.